History

A 28-year-old Asian woman is referred by her general practitioner (GP) with persistent vomiting at 7 weeks’ gestation. She is in her second pregnancy having had a normal vagi-nal delivery 3 years ago. She is now vomiting up to 10 times in 24 h, and has not man-aged to tolerate any food for 3 days. She can only drink small amounts of water.

She saw her GP a week ago who prescribed prochlorperazine suppositories but these only helped for a few days. She feels very weak in herself and is unable to care for her son now. On direct questioning she has upper abdominal pain that is constant, sharp and burning. She has not opened her bowels for 5 days. She is passing small amounts of dark urine infrequently but there is no dysuria or haematuria. There has been no vaginal bleeding. There is no other medical or gynaecological history of note except that she suffered per-sistent vomiting in her first pregnancy requiring two overnight admissions.

Examination

She is apyrexial. Lying blood pressure is 115/68 mmHg and standing blood pressure 98/55 mmHg. Heart rate is 96/min. The mucus membranes appear dry. Abdominal exam-ination reveals tenderness in the epigastrium but no lower abdominal tenderness. The uterus is not palpable abdominally.

Questions

• What is the diagnosis?

• What are the potential complications of this disorder?

• How would you further investigate and manage this patient?

The woman is suffering from hyperemesis gravidarum. This affects only less than 2 per cent of pregnancies, although more than 50 per cent of women report some nausea or vomit-ing when pregnant.

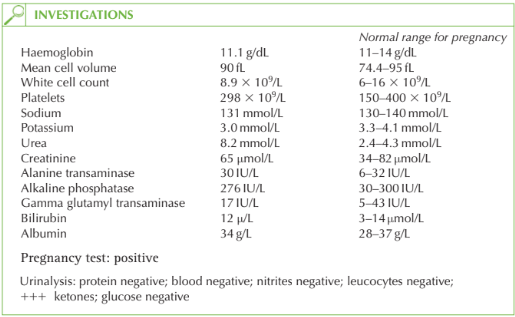

The diagnosis in this case can be made because the urinalysis is negative apart from the ketones, so urinary tract infection is very unlikely. She has not opened her bowels but this is likely to be secondary to poor dietary intake and dehydration. Liver function is normal, so liver disease causing vomiting is unlikely (though abnormal liver function may occur as a result of hyperemesis itself). Thyroid function is normal, so an alternative diagnosis of hyperthyroidism causing the vomiting is unlikely.

The fetus is not at risk from hyperemesis and the nutritional deficiency in the mother does not seem to affect development. The risk of miscarriage is lower in women with hyper-emesis. The risk of twins and molar pregnancy has traditionally been thought to be greater in women with hyperemesis, but this is refuted in more recent research. Further investigation and management Hyperemesis is a self-limiting disease and the aim of treatments is supportive, with discharge of the woman once she is tolerating food and drink and is no longer ketotic on urinalysis.

• Fluids: 3–4L of normal saline should be infused per day. Dextrose solutions are contraindicated as they may precipitate Wernicke’s encephaolopathy and also because the woman is hyponatraemic and needs normal saline.

• Potassium: excessive vomiting generally leads to hypokalaemia, and potassium chloride should be administered with the normal saline according to the serum electrolyte results.

• Anti-emetics: first-line antiemetics include cyclizine (antihistamine), metoclopramide (dopamine anatagonist) or prochlorperazine (phenothiazine). In severe cases, ondansetron or domperidone may be effective. There is no evidence of teratogenicity in humans from any of these regimes.

• Thiamine and folic acid: vitamin B1 (thiamine) can prevent Wernicke’s encephalopathy or the irreversible Korsakoff’s syndrome (amnesia, confabulation, impaired learning ability).

• Antacids: for epigastric pain

• Total parenteral nutrition (TPN): TPN is rarely indicated but may be life saving where all other management strategies have failed.

• Thromboembolic stockings (TEDS) and heparin: women with hyperemesis are at risk of thrombosis from pregnancy, immobility and dehydration, and should be considered for low-molecular-weight heparin regime as well as TEDS. Monitoring Daily monitoring should be carried out, with weight measurement and urinalysis for ketones and renal and liver function.

KEY POINTS

• Hyperemesis gravidarum is a diagnosis of exclusion.

• There is no adverse effect on the fetus.

• Treatment is supportive.

• Thiamine replacement prevents Wernicke’s encephalopathy and Korsakoff’s syndrome.

need an explanation for this answer? contact us directly to get an explanation for this answer