History

A 26-year-old woman is referred by the orthopaedic surgeons for an urgent dermatology opinion. Three weeks previously she had sustained a lower leg laceration at work and had attended the accident and emergency department where the wound was cleaned and sutured. Within four days the sutures had dehisced, so she presented to her GP who pre-scribed a course of flucloxacillin. Two days later, with an enlarging ulcer and increasing

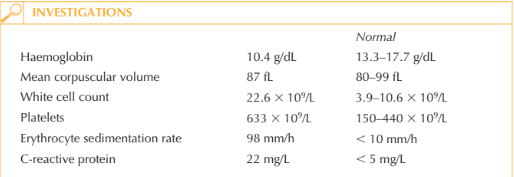

pain, she attended the A&E once more. The concern was of potential extending necrotic infection, such as necrotizing fasciitis and she was taken to theatre for urgent debride-ment and commenced on intravenous vancomycin and gentamicin. In theatre the ulcer was debrided but the base, surrounding skin and fascia were all noted to be healthy. She continued on antibiotics and daily ulcer dressing. There was no growth from any of the swabs or samples sent for microbiological, atypical mycobacterial, viral or mycological analysis. Over the next 10 days the ulcerated areas have continued to extend associated with extreme pain. She also complains of lethargy and arthralgia. She is a non-smoker and is otherwise well. She has no past medical history.

Examination

There is marked erythema and swelling of the distal third of the right lower leg, ankle and proximal foot. There are two areas of ulceration: a smaller regularly shaped ulcer anteromedially, and a more irregularly shaped and larger ulcer extending posteriorly from the medial malleolus (Fig. 43.1). Both have raised, purple to red inflammatory bor ders. The bases of the ulcers are covered with adherent yellow slough. The surrounding skin (particularly distal to the ulceration) is erythematous and there is marked swelling.

Pedal pulses are difficult to palpate on the affected side due to pain and swelling, how-ever bedside Doppler studies confirm good flow.

Questions

• What are these lesions?

• How can the diagnosis be confirmed?

• What is the management of this patient?

This presentation is not typical of many types of leg ulceration; both venous and arterial ulceration are easily excluded. The history of a penetrating injury followed by an enlarg-ing wound and pain must raise the concern of infection and/or foreign body reaction.

Necrotizing fasciitis is a progressive, rapidly spreading, inflammatory infection located in the deep fascia, with secondary necrosis of the subcutaneous tissues. It can be dif-ficult to recognize in its early stage, but without aggressive treatment is associated with a high mortality and morbidity even amongst previously fit and healthy individuals.

Other infective differential diagnoses include ecthyma (an ulcerative pyoderma of the skin caused by group A -haemolytic Streptococci) and sporotrichosis (a subcutaneous or systemic infection caused by Sporothrix schenckii, a rapidly growing dimorphic fungus). Cultures in this circumstance should be continued for at least six weeks before being declared negative.

The lack of positive culture despite provision of surgically obtained affected tissue sam-ples, as well as the lack of response to broad-spectrum systemic antimicrobial agents, makes infection unlikely. The clinical features would be consistent with the presentation of pyoderma gangrenosum. The diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum is one of exclusion, histopathological features can include massive neutrophilic infiltration, haemorrhage, and necrosis of the overlying epidermis; however, they are non-specific. Approximately 50 per cent of patients with pyoderma gangrenosum have an underlying systemic dis-ease such as inflammatory bowel disease, myelodysplasia, lupus or other autoimmune diseases. Full systemic work-up to exclude these conditions is essential, as treatment of the underlying disorder may improve the cutaneous features. Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum can be challenging. Surgery should be avoided, if possible, because of the pathergic phenomenon that may occur with surgical manipula-tion or grafting, resulting in wound enlargement. Topical therapies include gentle local wound care and dressings, superpotent topical corticosteroids and antiseptic precautions.

Systemic immunosuppression with agents such as corticosteroids, ciclosporin, mycophe-nolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide, anti-tumour necrosis factor agents such infliximab and even intravenous immunoglobulins are used. Adequate pain relief is crucial.

KEY POINTS

• Pyoderma gangrenosum is an uncommon ulcerative cutaneous condition of uncertain aetiology. Ulcerations of pyoderma gangrenosum may occur after trauma or injury to the skin in 30 per cent of patients; this process is termed pathergy.

• The diagnosis is made by excluding other causes of similar appearing cutaneous ulcera-tions, including infection, malignancy, vasculitis, collagen vascular diseases, diabetes and trauma.

• Therapy of pyoderma gangrenosum involves the use of anti-inflammatory agents, such as corticosteroids, and immunosuppressive agents.

need an explanation for this answer? contact us directly to get an explanation for this answer