A CHILD WITH A SQUINT

History

Rachel is a 9-month-old girl who is brought to her GP practice by her mother. Over the last month her parents have noticed that her eyes don’t always seem to be looking in the same direction. She was born at 35 weeks’ gestation after an emergency Caesarean section for suspected placental abruption, but was in good condition at birth. There were no medical problems after delivery. She had chickenpox 1 month ago, but has never really been to the surgery otherwise, except for her immunizations. Her mother reports that she his happy with her development, as Rachel is doing everything at about the same age that her 3-year-old brother did.

Examination

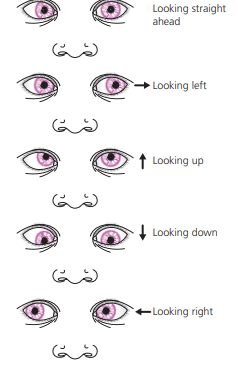

Rachel is a healthy-looking child. She has an obvious right convergent squint. Figure 73.1 illustrates the appearance of her eyes as she looks around.

Figure 73.1 Appearance of Rachel’s eyes as she looks around.

Questions

• What is a convergent squint?

• What are the possible causes of a squint in a child this age?

• What simple assessment can be performed?

• What should be done next?

Squint (strabismus) is a common problem, which may be intermittent or constant. The visual axes of the eyes cannot be aligned simultaneously, resulting in the appearance of one eye not looking in the same direction as the other. A right convergent squint (esotropia) means that the right eye is turned in towards the nose when the left eye is looking directly at a target. Squints may be paralytic or concomitant. Paralytic squints are caused by dysfunction of the motor nerves controlling eye movements (cranial nerves III, IV and VI). Whilst paralytic squints are rare, it is essential to recognize them, as they may be the first sign of a brain tumour or a neurological disorder. Concomitant squints are common and are usually due to extraocular muscle imbalance in infants, or refractive errors after infancy. The most common manifestation is the squinting eye turning medially. A concomitant squint can also be the presenting feature of more serious eye disease, such as retinoblastoma. Rachel has a concomitant squint. A squint can be confirmed by testing the corneal light reflex – shining a point light source to produce a reflection on both corneas and looking at the position of the reflection on each eye. Sometimes prominent epicanthic folds or a broad nasal bridge will create the impression of a squint (pseudosquint), but in this case the light reflex will be normal. The range of eye movements should be tested by moving a visual stimulus to determine if there is a paralytic squint – the affected eye will not be able to follow the stimulus in all directions. The red reflexes should be tested with an ophthalmoscope. Absence of the red reflex indicates ocular pathology such as a cataract or retinoblastoma. The cover test (see Fig. 73.2) should be performed to determine the nature of the squint. Whilst the child looks at a visual stimulus, each eye is covered in turn. The observer looks at the movement of the uncovered eye first, and then the covered eye as it is uncovered. When the fixing eye is covered, the squinting eye will move to take over fixation. Sometimes a squint may only be apparent when an eye is covered (latent squint) and this can be inferred from movement of the eye as it is uncovered.

Figure 73.2 Cover test

Mild and intermittent squint may be present in the neonatal period and disappear without treatment. Any child over 3 months of age with a squint, or parental concern about a squint, should be referred to an orthoptist or ophthalmologist for further assessment. The aim is to detect any serious underlying pathology and to prevent the development of amblyopia. In the developing brain, the image from the squinting eye is suppressed to avoid diplopia. In an untreated squint, this leads to irreversible suppression of the visual pathways, visual impairment in that eye and possible blindness. This phenomenon is known as amblyopia. Treatments include correction of refractive errors with glasses, patching of the good eye to force use of the other eye, and surgery on the extraocular muscles.

KEY POINTS

• Squint is a common childhood problem.

• It is essential to determine if it is a paralytic or non-paralytic squint

. • Referral to a specialist is important to prevent development of amblyopia.

need an explanation for this answer? contact us directly to get an explanation for this answer